A resurgence in psychedelic research suggests that psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms,” may help treat depression.

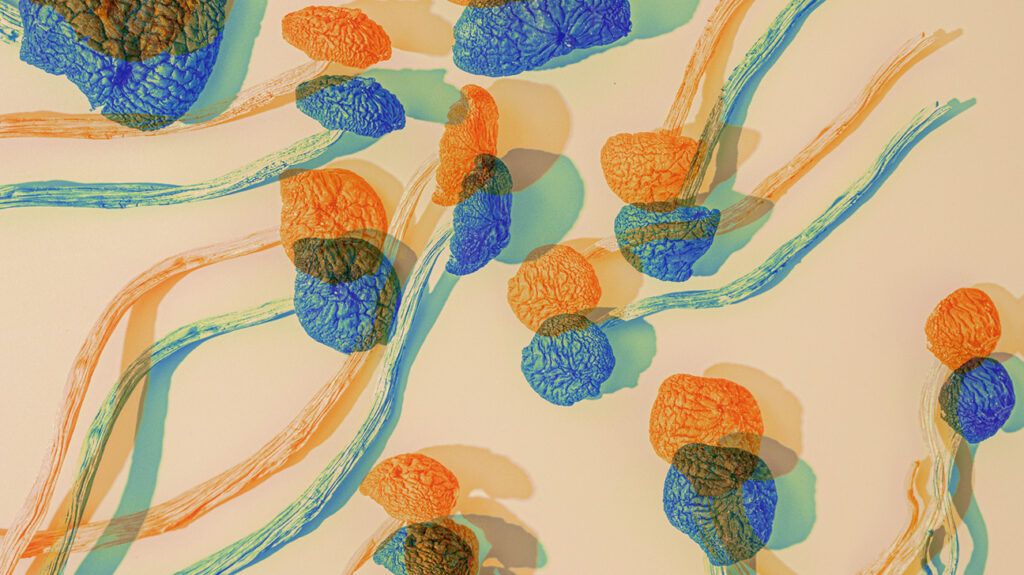

Psilocybin is the psychoactive chemical compound found in more than 100 species of fungi, also known as “magic mushrooms.”

During the 1950s, psychedelic researchers in the United States began studying the potential psychological benefits of hallucinogens, like LSD (acid), MDMA (ecstasy), and psilocybin (mushrooms). By the 1960s, psychedelics became famously popularized by psychologist and cult figure Timothy Leary.

In 1971, the Nixon administration responded to Leary’s championing of mind-altering drugs by declaring a war on drugs, which subsequently shut down most, if not all, psychedelic research.

During the early 1990s, some of that stigma began to lift, and a new generation of scientists revisited the mental health benefits of hallucinogens.

In recent years, psilocybin has reemerged as a candidate of interest for potentially treating depression and other diseases, like cancer.

“The potential therapeutic benefit of natural plant products like psilocybin is promising,” says Linda Strause, PhD, a clinical consultant for Emotional Intelligence Ventures (Ei. Ventures), a biotech startup developing a patch that could deliver psilocybin through the skin.

“The potential for these products, not just to treat but also potentially prevent mental illness from arising in the first place, would have a major impact on overall wellness in our population,” Strause says.

A handful of biotech companies, including Ei. Ventures, Psilera, Mydecine Innovations Group, and PsyBio Therapeutics, to name a few, are developing psilocybin and psilocybin-like drugs to treat psychological conditions.

Yet none have received full approval from the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the general population.

A note on psilocybin

No physician or mental health professional may prescribe psilocybin to treat a physical or mental health condition.

Psilocybin research must first garner approval from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

A psilocybin drug must also complete large-scale clinical trials and be tested and approved by the FDA for use in humans to be considered legal.

Magic mushrooms, or “shrooms,” are wild or cultivated fungi that contain naturally occurring tryptamine to produce a hallucinatory effect. They belong to a group of drugs known as psychedelics.

Magic mushrooms have been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years among indigenous peoples in South and Central America. Depending on the climate, magic mushrooms can also grow in parts of North America and Europe.

Similar to ayahuasca, shrooms are commonly used in many modern-day shamanic rituals or healing ceremonies and retreats in various parts of the world.

Under the Controlled Substance Act of 1971, psilocybin is classified as a Schedule I substance. According to the DEA, a Schedule I drug that has a high potential for misuse is prohibited for medical use and lacks safety for use even under medical supervision.

Possible effects

As a hallucinogen, magic mushrooms activate the brain’s serotonin receptors in the prefrontal cortex, which alters cognition, mood, and perception.

Common side effects of magic mushrooms include:

- a body high

- colorful visuals

- confusion

- drowsiness

- feelings of joy

- hallucinations

- introspection

- lack of coordination

- nausea and vomiting

- nervousness

- panic

- paranoia

- physical or muscular weakness

- psychosis

A growing body of research suggests that the psilocybin compound in magic mushrooms may help treat depression.

For instance, a 2020 review of clinical trials suggests that psilocybin could be considered a first-line treatment for depression, as well help with anxiety associated with diseases like cancer.

Results further indicate that the psilocybin compound may be effective in reducing symptoms in mental health conditions that are either treatment-resistant or for which pharmacologic (drug) treatment has not yet been approved.

Other research in 2020 showed similar results, but noted that the studies included were both small in size and had potential biases in findings.

Due to limited clinical evidence, not all experts have drawn conclusions.

“We have no idea if psilocybin works to treat depression because it’s not yet approved,” says Michael Spigarelli, MD, a pharmacologist and chief medical officer at PsyBio Therapeutics. “Studies have not yet been fully vetted.”

Spigarelli, whose research company is developing biosynthetic psychoactive compounds to treat mental health conditions and neurological disorders, including a psilocybin-like drug, explains that psilocybin shares a similar chemical structure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) used to treat depression, such as Zoloft.

“Psilocybin binds very specifically to certain serotonin receptors to make the serotonin you have in your brain last longer, similar to an SSRI, which makes it intriguing as a potential treatment,” he says.

Clinical trials

The existing scientific literature and an increasing number of clinical trials could show a promising future for psilocybin as a potential treatment for depression symptoms.

Like all clinical trials, psilocybin research must be conducted under an IND (investigative new drug) application and be registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.

The majority of psilocybin research for psychological support is still ongoing, but two recent clinical trials offer considerable evidence.

A phase 2 clinical trial from 2021 suggests that psilocybin may be as effective as escitalopram (Lexapro), a commonly prescribed SSRI, for managing depression.

A

The results are encouraging, but Strause points out that larger and longer trials are still needed.

The effectiveness of psilocybin must also be compared to antidepressants, and the data should be of statistical significance.

Recommended dosage

The appropriate dosage of psilocybin will vary depending on an individual’s symptoms and tolerability, and also depend on the product that’s being administered and its method of delivery.

In the clinical trial that compared psilocybin to Lexapro, Strause explains that patients received two separate doses of 25 milligrams (mg) of psilocybin 3 weeks apart.

Strause says that a transdermal patch such as the one being developed by Ei. Ventures could help to provide a steady, consistent dose to improve safety and efficacy.

“This will potentially eliminate the acute ‘peak’ experience while achieving the necessary threshold effects most associated with transformational change in a person’s mental health,” she says.

Other experts agree that delivering psilocybin in microdoses may be more effective, but there’s no real consensus.

“Microdosing seems to make sense if you believe there can be a therapeutic benefit without hallucinating,” says Spigarelli. “But some people say that if you have the spiritual hallucination experience once, then you can microdose after that to maintain the benefit.”

Spigarelli explains that the serotonin receptor associated with hallucination is known as 5-HT2A. Because SSRIs like Prozac can be effective without causing hallucinations, the jury’s out on whether hallucinating is necessary for psychological treatment.

“We know what it takes for someone to have a hallucinatory experience with psilocybin, but we don’t yet know what it takes to treat depression with psilocybin,” Spigarelli says.

“Maybe you would need psilocybin combined with other drugs or therapy, or maybe you need it on its own,” he says. “Maybe you need it once a day, week, or month — all of these questions would need to be laid out in a formal clinical trial protocol and require FDA approval first.”

Psychedelic-assisted therapy

A number of biotech companies in the psychedelic research space, including PsyBio, emphasize individual targeted therapy, including psychotherapy.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy combines the use of psychedelics and psychotherapy to improve mental health outcomes for individuals with depression.

During a psychedelic-supported therapy session, a predetermined dose of psilocybin is administered under the guidance of a specialized therapist.

Even with full FDA approval, however, psychedelic-assisted therapy may be hard to come by.

“The availability of qualified psychedelic-assisted psychotherapists is likely to be a limiting factor in terms of safe and convenient access,” Strause says.

Strause is a proponent of alternative therapies for treating mental health conditions like depression and chronic diseases like cancer. However, therapeutics used for mental health conditions, such as depression, may come with side effects and limited efficacy.

According to Strause, psychedelic drugs are more likely to cause a negative psychological reaction than a physical one.

“From a psychological perspective, psilocybin is capable of promoting intense perceptual changes,” Strause says.

Possible psychological side effects of psilocybin include:

- hallucinations

- synesthesia

- alterations in temporal perception

Strause explains that the incidence of adverse physical side effects of psilocybin, such as nausea and drowsiness, are similar to those experienced from the SSRI escitalopram.

Because there are no FDA-approved clinical trials, Spigarelli asserts that we do not yet fully understand the risks and possible interactions.

“I have confidence there won’t be any terrible side effects,” he says. “As a pharmacologist, my goal is to test any drug in humans to find the lowest possible dose to get the best effect, because side effects will also be dose-dependent (i.e., the lower the dose, the safer the drug).”

As with any Schedule I psychedelic drug, psilocybin must be fully approved by both the DEA and FDA for pharmacological purposes to administer to the general population, which can be a long and drawn-out process.

“Those who’ve started clinical trials are still in the fairly early, not pivotal, stages,” says Spigarelli. “So we’re talking years before we see psilocybin on the market — maybe two in the best-case scenario, or maybe longer, depending on results.”

In terms of public perception, Spigarelli says there will always be those who remember the “just say no” or “this is your brain on drugs” era of the 1980s, which is quick to peg hallucinatory drugs as dangerous.

“Certain segments of the population might not take the drug if they know they are going to hallucinate,” he says. “But some people will want it to be available over the counter for recreational use.”

Strause adds that educating healthcare professionals, potential patients, and the public is also key to reducing stigma against hallucinogenic drugs.

If the FDA were to approve large-scale human clinical trials for psilocybin or a psilocybin-like drug to treat depression, these drugs could be administered to humans to test for effectiveness and safety.

Once the FDA collects results of approved trials and determines data is sufficient, the drug would be approved for use, but only in the manner that it was tested for (for example, treatment-resistant depression or major depressive disorder).

“We don’t want to put drugs on the market that are more dangerous than safe,” says Spigarelli. “We’ve come a long way since Nixon.”