Monotropism is a psychological theory explaining attention allocation. If you’re monotropic, you likely have periods of time where your focus is pinpointed, and it’s difficult to switch to another task or idea.

If you’ve ever been told you have a “one-track mind,” it’s likely you have a tendency to focus on one thing at a time or don’t prefer to multitask. You may even find it very difficult to divvy your attention and focus before more than just one or two tasks or ideas.

This state of streamlined focus is sometimes referred to as “tunnel vision.” It can help you intensely focus on detailed projects, but it can also mean you might forget or delay important tasks in other areas of life outside of that focus.

While anyone can be considered monotropic, the concept is most popularly used as a model to describe the unique workings of the brain in autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

If you’re monotropic, you’re more likely to experience tunnel vision, and you’re less likely to shift smoothly between multiple areas of attention like someone who is polytropic.

If you have a monotropic attention style, becoming engaged in an interest usually results in what’s referred to as a “flow state” where you:

- feel content and fulfilled

- are zeroed in on what you’re doing

- aren’t aware of or influenced by unrelated stimuli

Monotropism was first presented as a psychological concept in a 2005 paper by Dinah Murray, Wenn Lawson, and Mike Lesser as a new framework for viewing cognitive processes in ASD.

Rather than presenting differences in autism as executive function deficits, monotropism supports neurodiversity. Differences in the function and structure of the brain in ASD create a unique neurological model that is not inferior or superior to what’s neurotypical — it’s just different.

In other words, being monotropic isn’t negative, and polytropic isn’t positive. They’re just two different types of attention styles.

Being monotropic means more than just a narrow field of focus, however. It also means finding it difficult to move between multiple areas of attention quickly or smoothly. This can make multitasking difficult in places like school or work, and you may find it a challenge to follow group discussions with rapidly changing topics.

For some people, monotropism can contribute to overwhelm as the monotropic brain works to keep up with an abundance of new sights, smells, sounds, and experiences.

Monotropism can present across all areas of your life. As a psychological theory, it has no set list of symptoms and is defined by shared experiences among people, such as:

- having “special interests,” one or two topics you’re extremely interested and invested in

- difficulty staying focused on topics not related to special interests

- not being able to follow complex conversations well

- feeling overwhelmed in situations with multiple stimuli

- missing deadlines and forgetting details in multitasking environments

- dedicating years or a lifetime to highly detailed work, like a research project

- regularly experiencing a flow state when you’re working on a task

- spending excessive amounts of time working toward nonessential goals, like solving a puzzle

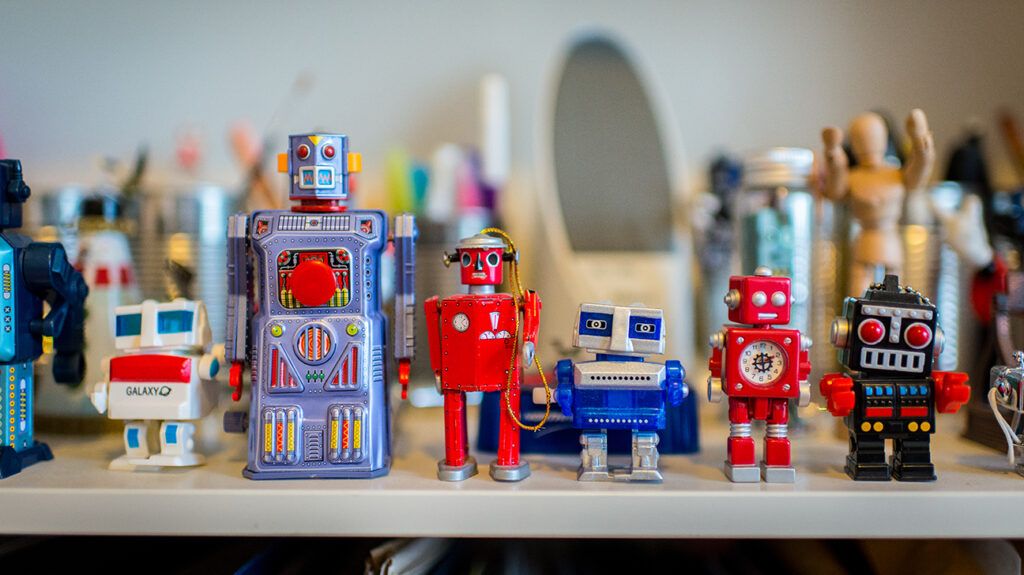

- creating and obtaining expansive collections related to a special interest

- being unable to stop reading an engrossing book

Sharing one or more of these experiences occasionally does not mean you’re monotropic. Monotropism is a pattern of singular attention marked by difficulty with rapid thought and task switching. If you’re monotropic, it’s present in your life consistently.

What is the difference between hyperfocus and monotropism?

Like monotropism, hyperfocus is

Hyperfocus is not the same as monotropism. Hyperfocus is a situational and temporary experience and not an underlying attention style that’s present all of the time.

Being inclined to focus on a singular idea or task can have a number of benefits. It can orient you toward detailed, high quality work and lead to mastery of a particular area of interest.

Because monotropic focus can mean being able to focus for long periods of time with one goal in mind, it can lead to deep engagement where you explore new theories or out-of-the-box problem-solving.

A

Monotropism can be challenging, but it also has many strengths. With the right support, you can help someone with a monotropic attention style find balance in task management and attention transitioning.

Ways you can support someone with monotropism include:

- showing appreciation for their areas of intense focus

- encouraging immersion in special interests

- helping establish a routine and predictable schedule with time for focused work

- working with them to break uninteresting tasks down into manageable steps

- minimizing distractions in the environment

- setting timers as cues to transition to a new task

- giving them notice ahead of time that task change is coming up

- encouraging breaks during periods of intense focus

- communicating clearly and allowing them time to respond

- initiating social opportunities with people who share specific interests

- connecting them with tools to help with organization, such as planners or calendars

- keeping deadlines flexible whenever possible

- checking in regularly to guide progress and support shifts to new tasks

- educating others about monotropism to promote empathy and reduce misunderstandings

Monotropism is a psychological theory that describes a single or narrow focus of attention style. While commonly used as a framework to help explain common experiences in autism, monotropism is not limited to ASD.

If you have a monotropic attention style, the following tips can help you effectively allocate your attention and transition between areas of focus when necessary:

- utilizing organization tools

- minimizing distractions in your environment

- establishing a regular routine for mundane tasks